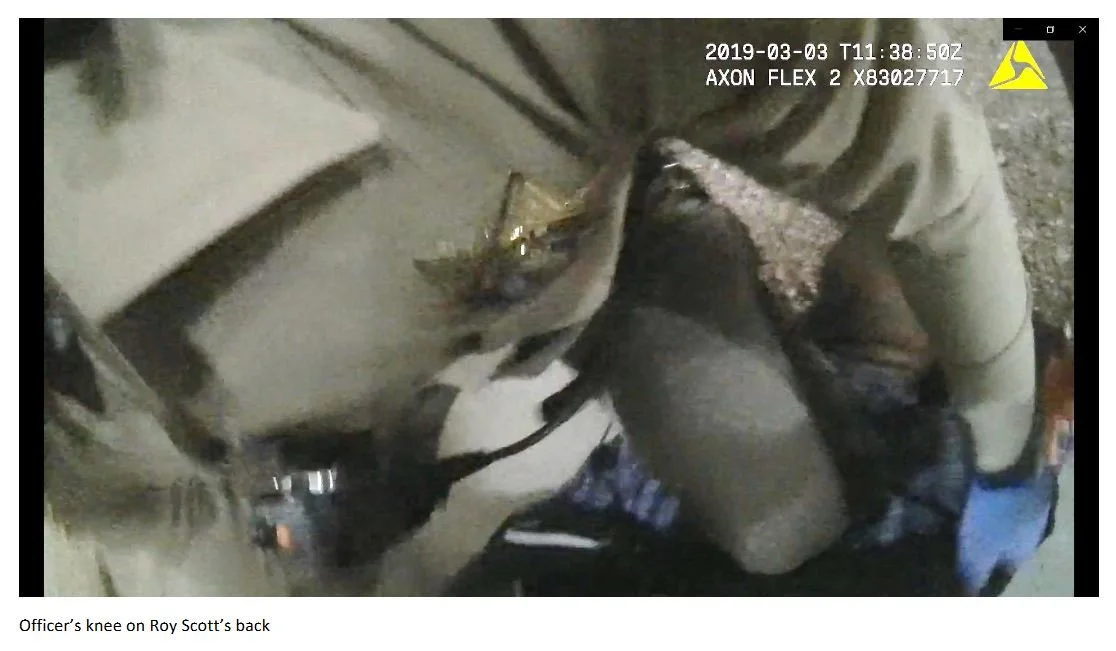

A recurring theme in videos of policing is the individual who refuses a law enforcement order to get out of a car. Often, these situations end with the use of force, even when the individual in the car isn’t doing anything affirmatively threatening to the officer.

The Sharp End of the Stick: A San Diego Police canine officer prepares to use the dog against a driver who refuses to get out of a car.

Sometimes this force tends, to the casual observer, to seem unnecessary or gratuitous. But is it “excessive” as a legal matter?

It depends.

The basic framework for this kind of question, as this blog has discussed before, comes from a multi-factor test set out in the 1989 case Graham v. Connor. To oversimplify somewhat, the standard for finding force to be “excessive” is a sliding scale. More force is appropriate when an officer is responding to a more dangerous crime and set of behaviors, while less is appropriate when these factors are absent.

The “getting out of a car” scenario is a subset of a larger group of cases that have to do with law enforcement officers ordering a person to come or go from some particular area and then using force when the person doesn’t comply, with other frequently seen examples including ordering inmates out of cells, ordering individuals to exit a room or a house, and ordering protestors to disperse from some particular area.

At least in theory, the mere act of passive “noncompliance” with a law enforcement order, in itself, does not warrant the use of “significant” force. Nelson v. City of Davis, 685 F.3d 867, 881 (9th Cir. 2012); Banks v. Mortimer, 620 F.Supp.3d 902, 925 (N.D. Cal. 2022). Therefore, the use of “intermediate” forms of force under those circumstances — with “intermediate” meaning things like baton blows or pepper spray — can be “excessive.” Sometimes the use of force against nonviolent protestors can be excessive for this reason, at least as long as the protestors really are in a mode of merely passively refusing to move and that noncompliance is the only crime at issue. The infamous UC Davis pepper spray incident, which was so over-the-top that it quickly became a meme (and which led to a $1 million settlement and policy reforms) is one such example of excessive force used against passive noncompliance.

Hot Ones: This 2011 use of pepper spray against merely passively noncompliant peaceful protestors at UC Davis during the Occupy Wall Street movement became famous because of the remarkably casual approach of the officer to the use of excessive force. Photo by Louise Macabitas.

But when it comes to individuals refusing to get out of vehicles, there are often other factors at play. In particular, these sorts of situations can sometimes occur in the context of traffic stops where the person in the car is suspected of having committed some other crime, up to and including a felony. That can change the force calculus significantly under Graham since felony traffic stops are treated as a high-risk situation for officers.

In the incident shown in the still above, officers used a police dog against a man who refused to get out of a stolen car on the side of a freeway after the use of verbal commands and pepper balls had already failed to produce any compliance. The entire freeway was shut down in one direction for about half an hour while officers tried to resolve the situation. The dog ultimately bit and injured the man, who was then pulled out of the car. The use of a canine is at least “intermediate” force and has been described as the most severe force authorized short of deadly force. Police dog bites can sometimes be incredibly damaging, in part because officers do not always have that much control over the animal once it is released. Fortunately, the man’s injuries, though significant, were not too extreme in this case.

In this situation, it is possible to Monday morning quarterback and think of other ways the man could potentially have been removed from the car. However, the fact that a serious degree of force was used was not necessarily “excessive” under the circumstances. The more iffy scenarios occur, typically, when the underlying offense leading to the interaction at the car is quite minor and there are alternatives available to the officer short of using a significant degree of force.