While law enforcement officers do not need any evidentiary basis merely to speak to a person on the street, they do need to have a specific, particularized basis to carry out investigative detentions. If law enforcement carries out such a detention in the absence of a particularized basis for “reasonable suspicion” that a person is engaged in some kind of criminal activity, the detention can amount to a Fourth Amendment violation and be the basis for civil liability.

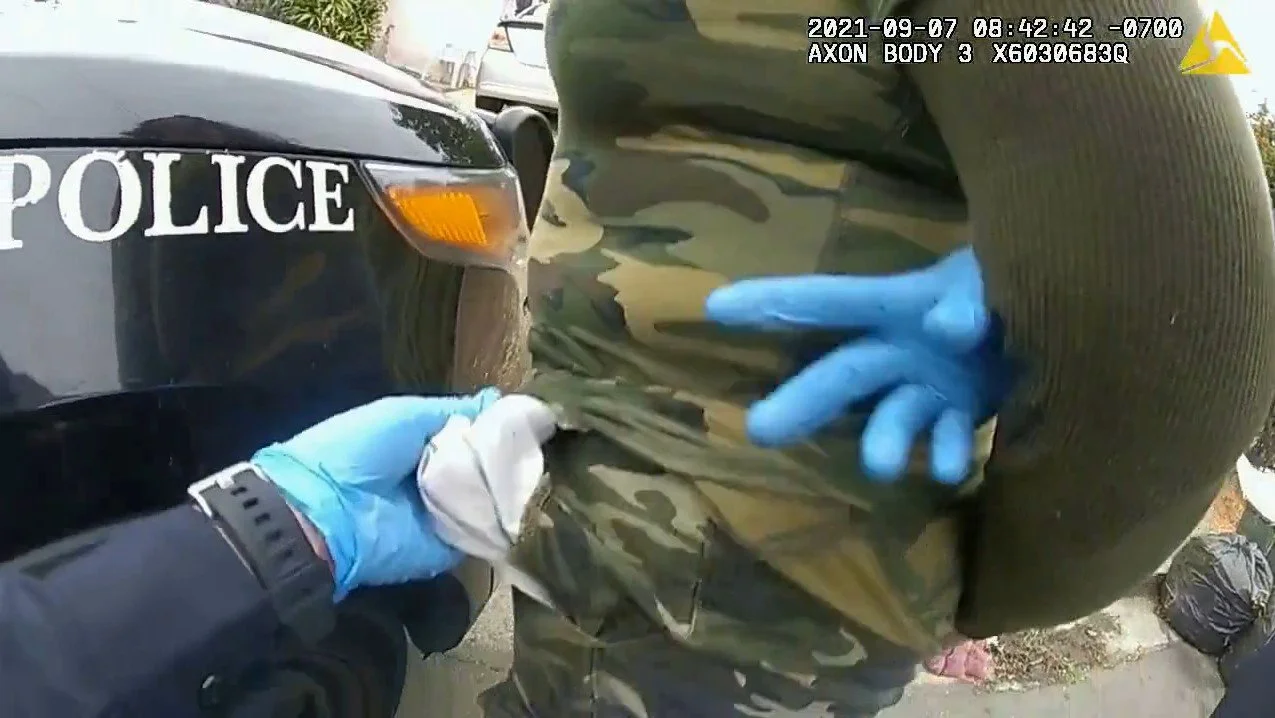

Inside Out: officers need particularized evidence of a crime to carry out investigative detentions. The scope of further searches that are permissible in such detentions, such a pat-down and rifling through the pockets, is a tricky, fact-based issue.

An investigative detention, which is sometimes called a Terry stop in the context of policing on the street, does not need “probable cause,” which is the level of evidence needed for an arrest: it will be legal as long as it is supported by “reasonable suspicion,” which is somewhat less granular than probable cause but nevertheless needs to be anchored in objective circumstances known to the officer and particularized to the individual being detained. The existence of such a stop depends on the totality of the circumstances and is triggered when a reasonable person would not feel “free to leave.” Brendlin v. California, 551 U.S. 249, 255 (2007). The analysis of that last factor is a little different than what common sense might imply, because most people don’t feel free simply to walk away from a police encounter under any circumstances. But the analysis does not begin and end there. Since it is a “totality of the circumstances” consideration, it looks to factors like the existence of multiple officers in the interaction, time and location, verbal commands, brandishing weapons, using handcuffs, using illumination (such as a spotlight) that makes a person understand they are the target of focused suspicion, and so on.

Another common variation of this standard occurs in a traffic stop, which also needs to be supported by “reasonable suspicion” that an occupant of the car has engaged in a crime, and has been explicitly analogized by the United States Supreme Court to a Terry stop. Rodriguez v. United States, 575 U.S. 348, 354 (2015).

Assuming an investigative stop is supported in the first place, a recurring issue in this area is what sort of searches officers can then carry out on the detained person or the items in their possession. Under Terry, it is generally acceptable for officers to carry out a pat-frisk of the detainee to ensure that they are not armed, if there is some specific basis to be concerned about weapons. Terry, 392 U.S. at 27-29. However, “A lawful frisk does not always flow from a justified stop.” Thomas v. Dillard, 818 F.3d 864, 876 (9th Cir. 2016), as amended (May 5, 2016) (quoting United States v. Thomas, 863 F.2d 622, 628 (9th Cir. 1988)). Rather, “[e]ach element, the stop and the frisk, must be analyzed separately; the reasonableness of each must be independently determined.” Id.

An initial pat-frisk can then give rise to bases to go through a person’s pockets, but it may be illegal for an officer to simply turn out a detainee’s pockets without performing any sort of pat-frisk or having any other reason to think that the contents of the pocket are an officer safety matter. United States v. Brown, 996 F.3d 998, 1009 (9th Cir. 2021); Sibron v. New York, 392 U.S. 40 (1968). In a similar vein, bags and purses carried by a detainee can be frisked where there is reason to believe that the bag may contain a weapon or contraband related to the crime that is being investigated. However, a investigative detention is not, in itself, a license for law enforcement to go rifling through a bag and just see what might turn up.

Fourth Amendment violations can also arise when a detention is unreasonably prolonged after reasonable suspicion of the original crime that supported the stop in the first place has been dispelled, such that the continued detention is little more than a fishing expedition for some sort of miscellaneous wrongdoing. Unreasonably prolonged detentions are a common theme of traffic stops, because the United States Supreme Court has given law enforcement the green light to carry out “pretextual” traffic stops (in which there is some technical violation, like a broken taillight or an illegal window tint, that supports the stop but the officer is actually looking for something else), and the officer who carries out such a pretextual stop will often then look for a reason to keep the stop going, to carry out searches of the vehicle, and so on, even when the driver really ought to be ticketed and released.

Needless to say, investigative detentions, and people’s responses to such detentions, are also the scenario that gives rise to many forms of use of force, and sometimes excessive force.

For free consultation about potential civil rights cases, call today.